In June 2020, the team coordinating the Homemade Mask Virtual Summit at Tulane University interviewed Dr. Songer about the science behind masks and invited Dr. Songer to give the Keynote Address for the summit. This post contains the audio and transcripts of Dr. Songer’s Keynote Speech: “Masks Unmasked: A Look at the Science Behind Fabric Masks for COVID-19” as well for the two interviews with Dr. Songer for the JustWannaQuilt Podcast. The “Homemade Mask Guide“, created in collaboration with both scientists and sewists after the summit is also included.

Keynote Address for the Homemade Mask Summit

Speaker Introduction: Dr. Jocelyn Songer is the founder of MakerMask.org, a group of volunteers providing science-based mask information and designs to community mask makers by studying and testing them. She holds a BS and MS in Biomedical Engineering from Worcester Polytechnic Institute and a PhD in Speech and Hearing Bioscience and Technology from MIT.

Keynote: “Masks Unmasked: A Look at the Science Behind Fabric Masks for COVID-19”

Dr. Jocelyn Songer

June 17, 2020

Keynote Speech Transcript

This has been edited for clarity and brevity. Each numbered subheading refers to a slide number

Audio Available at: https://www.spreaker.com/user/10136802/hmms-part-1-6-18-20-11-06-am

Introduction

1. Masks Unmasked (Illustration: 3 MakerMask Designs)

It was really fun listening into the last couple talks. I absolutely agree that masks are awesome and that perfect is the enemy of the good. That’s something I remind myself all the time; it’s not worth trying to make things perfect if you can’t get anything done. So the masks and emergency equipment that you have with you that you’re willing to wear is always going to be the best mask.

2. Thank You! (Illustration: Sewing Superhero)

I just wanted to say thank you “sew”, so much. None of us expected for sewists to be put on the front lines of equipment that everybody needs to be safe from this pandemic. But when global supply chains failed, sewists and others stepped up. I wanted to put in here how many masks we collectively have made. It highlights a little bit of the challenge with the science because it’s really hard to get solid numbers on that. At least, I wasn’t able to. It was like 70,000, 80,000, 100,000, but we don’t have any good totals of how many masks are out there that we’ve made, what they’re all made of, and all of that. But anyway, thank you “sew”, so much; you are true heroes of this pandemic and of 2020. I appreciate you and I know everyone else does as well.

My Story

3. My Story: A culture of Sewing (Vintage Postcard: Sewing in Orange c. 1880)

I am from a small town called Orange, Massachusetts. It is the home of New Home Sewing Machine. They started manufacturing sewing machines in my town in 1860. So sewing was a part of the culture that I grew up in. My grandma was a seamstress; my mom sewed all my clothes for me as a kid; she also sewed my prom dress and my wedding dress. I don’t think of myself as an awesome sewist, but I don’t remember a time when I didn’t know how to sew. My mom and my grandma constantly lecture me to stop sewing with a lead foot – if I want straight seams, I have to slow down.

4. My Story: Science & Engineering (Photo: Dr. Songer in the OR)

I know Whitney gave me a great introduction talking about my background as an engineer. I also have a background as a first responder; I used to be an EMT, and I maintain a current first responder training. So I never leave my house without some personal protective equipment and masks in general. I always have a sewing kit.

5. My Story: Occupational Asthma (Photo: Dr. Songer on Mt. Katahdin, AT 2013)

I was going along with my life in academia between engineering and biomedical stuff, and I developed occupational asthma; I was literally allergic to my job. So then instead of just having to use masks for work, I had to wear them for my own health. I got fitted with N95s and took contamination showers every day, but it wasn’t quite enough. My pulmonologist gave me a choice: I could either keep breathing or keep my job. So I left my job to go hike the Appalachian Trail and get my health back.

6. My Story: Backcountry Masks (Photo: Dr. Songer on PCT and CDT with Masks)

That is when I first started having some MacGyver masks and figuring out how to make a face mask that would filter smoke. Because while I was out backpacking the Pacific Crest Trail and the Continental Divide Trail, there were massive forest fires. I didn’t have access to supply chains for face masks because it would be another five days until I get to town. So I had to figure out how to make do with what I had. So I used two layers of my bandana hoping that it would work to filter out some of that smoke. It doesn’t work very well. So that sort of forced me to start improvising through other options with the materials and fabrics I had.

Then when I got off the trail, I did a whole bunch of research on masks and what the ideal combinations were. I think I purchased every single reusable facemask that was on the market at the time. So now I have a stack of all these different reusable facemasks, and I kind of had a sense of what did and didn’t work and what I liked and didn’t like. Masks with exhalation valves work well in a lot of situations like forests when you’re dealing with smoke; they don’t work great for infection control. What we’re using masks for now is to keep our germs to ourselves, essentially, and the exhalation valve just spews everything past the filter into the environment.

When we started to see supply chain shortages, I started working with my mom who’s an RN and a risk manager on researching and designing masks for COVID-19; trying to figure out what the best available information was and how to move forward; make sure that we could get these masks out to the loved ones in our community.

COVID-19 and Masks: Overview

7. Research on Handmade Masks Pre-COVID (Photo and Data from Research)

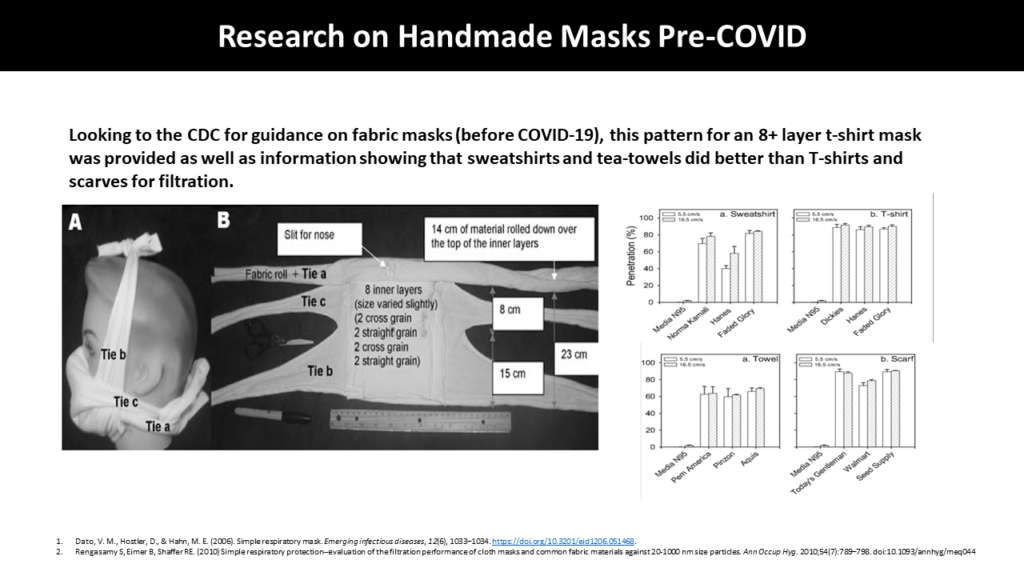

If you were doing research on handmade masks before COVID, you probably came across the same two studies: The one the CDC pointed everyone to that said it’s possible that we might end up wanting masks and not be able to get them in a pandemic – which turned out to be prophetic – and they gave this one pattern. In all of the literature at the time, I could only find one pattern for a handmade mask for an eight-layer cotton t-shirt mask. Calling it a pattern was perhaps a little bit of a stretch. It’s a picture of how they did the ties on it and sort of mentioning how they crisscrossed the t-shirt layers. That was the primary article the CDC cited. There was another one saying: Here are your fabric options: sweatshirt, t-shirt, towel or scarf.

Of those, they said the towel would be the best. I thought we had to be able to do better than a towel because towels wrapped around your face are not easy to breathe through and work with. If you’ve had the experience of hiking 100 days through the desert with a facemask, you’ll know that there’s a whole lot more to a facemask than whether or not it can pass a particle count; you have to be able to wear it, and wearing a really heavy, bulky mask for long periods of time isn’t practical for most people. So I looked at that research and said let’s see if we can do better. The next thing that was important was seeing what we knew about how COVID was being spread.

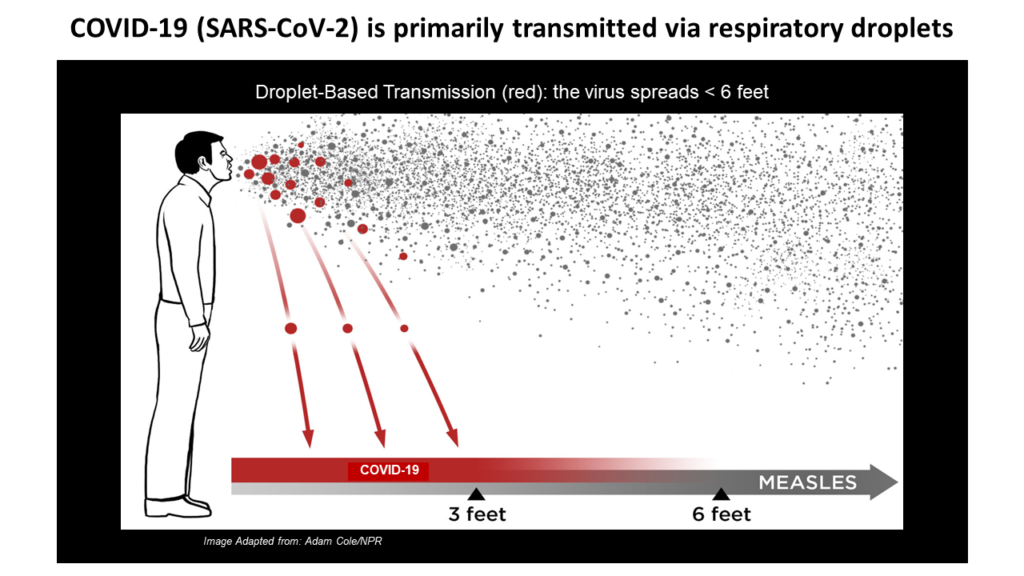

8. COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) is primarily transmitted via respiratory droplets

The WHO, CDC and all the research we have so far suggests that COVID-19 is primarily spread via respiratory droplets. There’s a figure here that was originally for Ebola but is also true for COVID showing that the droplets spread around six feet. If you’re talking about something that is airborne and truly aerosol driven, the distance that you’re talking about is 30 feet instead of 6. So the main thing we wanted our masks to do was to block droplets.

In Healthcare Settings, Medical Masks are Used for Droplet Precautions

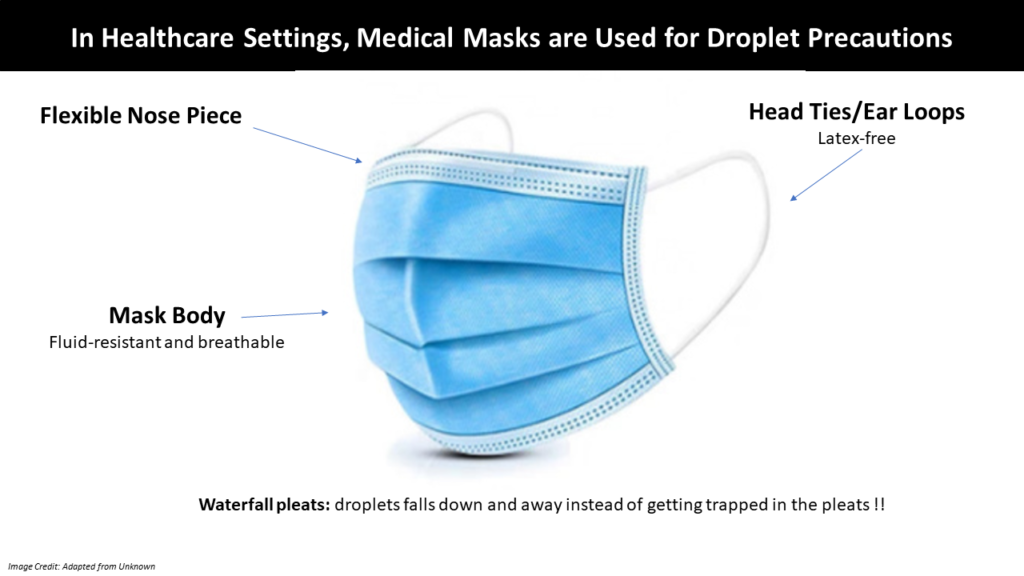

I know that the previous speaker was talking about focusing on masks for the general public and not on the kinds of masks that you need in healthcare settings, and I was kind of interested in bridging that gap. Right now in healthcare settings, medical masks are used as droplet precautions. What that means is that depending how a disease is transmitted, there are different recommendations and guidelines for the precautions that you need to take so as to keep you safe as well as your patients.

So, the kind of mask that is suggested for things that are droplet-based is usually a surgical mask because they block those large droplets that we were talking about.

9. Anatomy of a Mask

Flexible nosepiece to help get a better fit across the bridge of the nose; ear loops (must be latex-free because a lot of elastic has latex in it and a lot of healthcare providers have latex allergies); body of the mask.

A lot of the dialog focuses on particle filtration, but for droplet precautions, fluid resistance is a key component of the mask requirement, as is breathability. The way that you test this if you’re trying to attain a surgical mask certification is with blood – synthetic blood at 80mm mercury pressure sprayed at it. So one of the things that I’m hoping to get dialog on with some of the regulatory agencies is setting up standards that are not surgical masks so you don’t have to have it withstand 80mm of mercury blood, but they’re still fluid resistant. If you’re getting sneezed or coughed at, or somebody spits at you, it’s not coming at that same high pressure.

I see a lot of masks online and in the news that are worn upside down where the pleats are backwards. The waterfall pleats should fall away from your nose. If the mask is upside down, that leads to the possibility of things getting caught up in those pleats instead of falling off and away from them. I call those tide pool pleats because they gather things inside the mask.

10. For the General Public, Fabric Masks are Used to Prevent the Spread of Droplets

When we’re looking at facemasks for the general public, the WHO and the CDC now agree that we should be using facemasks in general and that these facemasks are designed to prevent or reduce the spread of COVID-19. So you place your face covering on to protect other people, and they place their face covering on to protect you. So that’s the intended use for facemasks now. The FDA says that when you’re talking about fabric masks and cloth face coverings, you should remind people that they’re not replacements for social distancing and hand hygiene.

11. Research: Face Masks Help Reduce the Spread of COVID-19!

In just the last couple weeks we’re getting some studies coming out that say yes, indeed, the facemasks are working. Not only do medical masks help but cloth facemasks and fabric masks also help. A study of 172 articles is what made the WHO change their mind and say yes, we do recommend fabric masks.

Just within the week we got this new study saying that wearing a facemask in public corresponds to the most effective means to prevent human transmission of COVID-19. That is pretty huge. They show that within a month, 70,000 infections were prevented in Italy and 66,000 in New York. Looking at these graphs, on the left there’s a picture of data from the US that shows the effect of social distancing at flattening the curve, and on the right they show the data from New York City which shows that instead of just flattening the curve, putting in the facemasks requirements and getting people to adopt facemasks on a large scale crushed the curve; instead of being flat, you got a decrease in infection.

So, the fabric masks that we’ve been making, they have helped and they are helping. The data is finally coming through showing that. We are making a difference, and that is awesome and important.

Mask design Requirements

12. My Fabric Mask Requirements: Water-Resistant, Breathable, Washable, and Latex-Free

I founded MakerMask. My mom and I designed some masks as we were going through the options. The requirements I was looking for were that they be water resistant, breathable, washable and latex-free. The big difference there compared to most medical masks is washable, because in healthcare settings masks are traditionally single use. That’s led to some interesting design features. One big challenge because I was looking for water-resistant materials was balancing water resistance and breathability because those two things do not usually get along; waterproof is not breathable, and breathable waterproof materials aren’t really waterproof. So that’s an interesting tradeoff. From my backpacking experience I had already done a bunch of research into different fabrics where you can get this tradeoff.

13. Spunbond Nonwoven Polypropylene

I ended up landing on nonwoven polypropylene. Spunbond is the kind of polypropylene you’re looking for, and we like it synthetic not woven. That combination allows it to be breathable, which is good. Nonwoven structure helps with filtration; nonwoven materials tend to be better at the mechanical filtration component. The nonwoven polypropylene (NWPP) materials are water resistant; they’re naturally hydrophobic. The spunbond nature of the fabric has better structural integrity and is continuous fibers. A lot of you who’ve been paying attention to mask filter materials have probably heard about meltblown polypropylene as well, which uses smaller, more discontinuous fibers that don’t hold up to washing. The fibers can shrink and compress, and you lose breathability. So that’s how I ended up with that spunbond NWPP. The other advantage to the NWPP at the time was that I had it lying around the house; I could source it from reusable grocery bags that I had or from a whole bunch of other options.

14. CDC Guidance on Cloth Face Masks

I could give a three-hour talk just on NWPP, how it’s made, it’s features. Ideally, we would be using medical-grade NWPP, which we can’t get because of global sourcing issues. My next criteria was food-grade NWPP because it’s designed to touch food and gives you some better hazard analysis parameters, essentially. There are other materials that are heavier and others that look similar that aren’t quite as good, so you need to make sure you check breathability. Maybe we can find a time to talk about all the dos and don’ts of how you go about making those finer choices.

On the CDC’s webpage, they say masks need to be multilayer. They’re recommending tightly-woven cotton. All of their designs are cotton, which is an absorbent material, which is good at containing your droplets and keeping them to you. I don’t want to talk about their bandana mask design because it drives me nuts.

So, it has to be multiple layers; you should check to make sure it’s breathable and washable. The FDA requires that you include a label in the skin-contacting material with washing and disinfecting instructions.

WHO Guidance on Fabric Masks

15. WHO Guidance on Fabric Masks

There is a lot of discussion about the WHO guidance and why they recommend what they do. They recommend at least three layers of mask materials with an outer-most layer that’s hydrophobic (water resistant. The way people measure it is by looking at how well water beads up on the surface of the material. If you can see a full bead of water sitting on top of the material, that’s hydrophobic; if water absorbs into the material like a paper towel, that’s hydrophilic. Hydrophobic and water resistant tend to mean the same thing, and hydrophilic and absorbent mean roughly the same thing as well. Synthetic materials, for the most part, are hydrophobic. Silk and cotton fibers are hydrophilic. Flicking a bead of water at it is the way I tend to make my first approximation. Pour 5ml of water from a teaspoon to see if it drains through within 60 seconds is the more quantitative way of assessing that.

When the WHO guidance is saying polypropylene or polyester, those materials are selected because they’ve tested them and they have that hydrophobic property in the threads. If you have a knit t-shirt with holes in it that’s made out of polypropylene or polyester, even though the fibers don’t absorb water, the material isn’t water resistant so the water can go through the holes.

Elizabeth Townsend Gard, Host: So if you’re shopping somewhere like Jo-Ann’s, they’ll say what it’s made out of, so this is very helpful in terms of moving forward. So this is doable for us as sellers.

Songer: Absolutely! We have already talked for 2.5 hours and this is another half an hour, but I would love to gather information and have some more conversations so we can bridge some of the communication gaps across the communities.

ETG: One of the things is to put out a Best Practices for the sewing community that’s very short and simple but helps people understand how to pick the fabric and what the key things are. I’d love for you to work with us on that. It’s basically what you’re doing but put it into sewing language so that we can actually have this discourse. I really do believe that you help us make this very difficult bridge between the science and the sewing community.

Songer: For that outermost layer with the waterfall pleats, if you can, you want things to hit it and drop down and away instead of getting absorbed into the mask and held close to your face. So the goal of the outer-most layer is to prevent things from going into the absorbent layers. The WHO is specific in suggesting that the outer-most layer be hydrophobic. That’s a pretty major difference from the recommendations we were seeing before this new guidance. Those were 100% focused on source control – containing the user’s droplets. That’s still the intended use for all of these masks, but it’s raising the possibility that you might actually be able to prevent at least some stuff from coming through the other way.

For the middle layer, you can go either way. They say either use a hydrophilic layer like cotton or a cotton blend that will absorb the user’s droplets or use a hydrophobic nonwoven material which will enhance filtration. They say that because nonwoven materials have a much more chaotic structure and do better at mechanical filtration than woven materials because woven materials tend to have holes that go straight through in a more organized way. So if you’re used to doing materials at different angles, that mismatch of how the fibers are formed together gives you better filtration. There’s lots of literature on the different nonwoven materials, but that’s the rationale there.

For the inner-most layer in masks for general use and for surgical masks as well, that is designed to contain user droplets. So, they recommend a hydrophilic or more absorbent material like cotton.

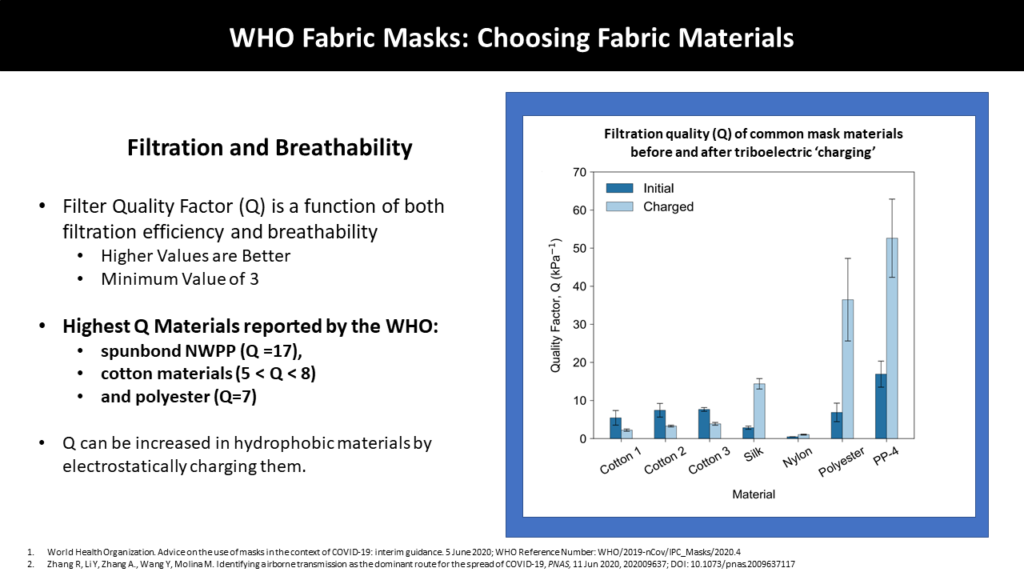

16. WHO Fabric Masks: Choosing Fabric Materials

One of the differences between the guidance we got from the CDC and what we’ve heard from the WHO is that the WHO starts giving us actual criteria for how we should be choosing materials for fabric masks. The reason why they select among NWPP, polyester and cotton in specific is because of a new study that came out in ACS showing the balance between filtration and breathability – those two things can be measured separately, but in order to kind of look at them both together, they ask you to look at the filter quality factor because that combines both metrics in one. So, the higher the Q value, the better. You want Q values for the materials you’re using to be greater than 3. That is a criteria that we can look for to have a good balance between filtration and breathability. Because if you can’t breathe through it, it doesn’t matter how good the filtration is; you can’t use it in a mask.

They show the Quality factor for three different cotton materials, a silk material, nylon (which doesn’t do very well at all,) and polyester, and spunbond nonwoven polypropylene. For each material, they show the initial value off the shelf, and then they check to see if you can improve Q values with an electrostatic charge. You can think about it as static electricity. That’s what they test in this particular study. Back in high school/college physics, you’d do demonstrations rubbing materials against a rubber rod and build up a charge on it and then show that the material gets a static charge and keeps it for some amount of time. When you do that with cotton, it doesn’t build up and hold an electrical charge; if you do it with a hydrophobic material like polyester or polypropylene, not only does it hold a charge initially; it can keep the charge. Polypropylene was able to do that for longer than anything else. That allows it to be better at filtering. The thing that was most interesting about that electrostatic charge part is that they show that even when it started to get humid, the charge on polypropylene remained for over an hour. So it’s possible that there might be some practical applications for home users being able to electrostatically charge their masks. As an electrical engineer, it’s fascinating; I’m really interested to see how that pans out long term.

ETG: I don’t really understand how it only lasts an hour. How are you supposed to recharge it? Are you supposed to have a bunch of masks with you?

Songer: I think that’s a fair concern, and it’s something I’m not sure about, either. They were showing that if you had a pair of vinyl or latex gloves and you rubbed your polypropylene mask between them, it would build up a static charge that was big enough that even at body temperature and humidity, you got the benefit of that for at least an hour. They didn’t show us data about what happened beyond the end of that hour. We don’t have information on how quickly that can cause a mask to break down because rubbing materials tends to cause them to break down faster. So that electrostatic component for home users I think is still an amazing, wonderful, fun theory, but the practicality of it still needs more consideration. But I think for instances where you’re going to go out for 15-30-60 minutes to run errands, and then you’re going to go back to your safe environment, it may be useful. More testing is needed. If you’re going to be wearing a mask for four hours, then that electrostatic boost you get isn’t likely to stay with the material the whole time. I looked at the data they have for the decay over time. It’s promising, but it needs more practical consideration.

Even without that electrostatic boost, the Q value for the nonwoven polypropylene is still the highest of all the others. The Q values that I mention in the summary are without the electrostatic charge. So that puts NWPP on the top of the list, cotton next, and then polyester somewhere in between. The nylon wasn’t breathable enough, so that’s why they voted no on that. The silk didn’t have enough filtration for them.

17. WHO Fabric Masks: Choosing Layering Combinations

Since early March, the very first thing I wanted to do was to get my mask designs tested. I did some basic hazard analysis to see if there were any obvious pitfalls because I wanted to make sure things were safe. There wasn’t any guidance on the ideal mask and what we should be aiming for in terms of testing criteria for fabric masks. The WHO guidance provides us some standards which we should be trying to adhere to in the design of our masks.

The WHO recommends at least three layers. A big part of that is adding that water-resistant, hydrophobic material to the outside. So, if you have a whole bunch of cotton masks and want to bring them up to WHO requirements, the only thing you need to do is add a mask cover of NWPP.

In terms of filtration, they say that for private masks for general use you should be aiming for 70% filtration efficiency. It’s nice to have some numbers there for what’s reasonable to get. For breathability, they suggest that you need less than a 40 Pascal pressure drop across the mask. That’s not easy for us to test at home. I have some data that I’ll share which shows that cotton masks and the cotton-NWPP combinations that we’re using do meet those criteria. For home users, I recommend putting your materials on the end of a toilet paper tube and blowing a ball of lint through them so you can test the breathability without having to put the mask up to your mouth and sucking air through it.

For the filtration, we don’t have access to the fancy equipment that the big testing labs do; we do, however, have access to our kitchens. For a lot of food stuffs, they have to calibrate the size of the particles. For those of you who both bake and sew, you know that having your baking soda and flour and baking powder at the right density makes a difference. Baking powder has particle sizes calibrated at less than 50 microns. You can find things in your kitchen with particle sizes down into some of the smaller-micron particles that are relevant. It can give you a sense of how well they’re doing. If I take the same toilet paper tube that I use for the breathability test and put it over the end of the material, for loosely-woven cottons you’ll see that the baking powder just shakes right through and makes a mess if you’re doing it on a piece of black paper. If you use a more tightly woven cotton, or two layers of it, or the NWPP, you can see that you don’t get as much going through. There are a bunch of other DIY home tests that people are looking at to try to get at that same small particle filtration.

Mask Care, Cleaning, and Disinfection

ETG: This is just the beginning of the conversation. We have questions about all kinds of other materials. We are going to be working with you if you’re willing to help people understand what these tests are and start to really think about the combination of fabrics that are out there as far as filtration, breathability and cost.

Songer: We’re designing fabric masks to be reusable and washable, and that’s a pretty big difference from what we’ve seen in the medical-grade masks. The WHO guidance references a French standard, which says that you need to make sure that your masks can hold up for at least five washes. That’s kind of a minimum for reusability. Then they suggest you need to be able to wash it at temperatures of at least 60C. I could give a whole talk on just the washing, cleaning and disinfection methods. The WHO and CDC recommend washing at the highest temperature you can. The WHO goes on to say that you can boil or steam combinations of cotton and NWPP. That’s important because that gets you a higher level of disinfection. COVID is somewhat sensitive to heat, so you don’t have to have the highest heat ever to kill COVID. But when you’re talking about a fabric mask that you’re putting over your mouth and reusing, COVID isn’t the only thing that can grow on that or accumulate on it. For some of the bacteria and fungi and spores, I’d like people to at least consider that you might want to periodically be killing off everything that could be growing in your mask and not just COVID. That’s something to keep in the back of your mind when you’re thinking about how you’re washing and cleaning things. When you’re putting things on your face multiple times, detergents become important as well. One of the biggest hazards with laundry in clinical settings is the buildup of detergent residues, which commonly causes skin allergies and irritation. So you want fragrance-free, low-residue detergents.

ETG: We have a question: Couldn’t you just wash the mask with hand soap for 20 seconds like you wash your hands? How is it different?

Songer: When you’re washing your hands, your skin is a fairly impermeable surface; water doesn’t absorb deeply into your skin. As you wash, what you’re mostly doing is rinsing everything off your hands and flushing it down the drain. When you’re dealing with cotton or any multilayer mask, you need to be making sure you’re getting at all the area that’s in those in-between layers and through all the seams and penetrating deeply through all that and anything that’s gathered in the pleats.

ETG: Can you iron polypropylene? Are you worried about that?

Songer: The short answer is you can iron it at the lowest setting on your iron; if you iron at a higher setting, it will melt. I have a Disinfection post on MakerMask where I went through the different temperatures that your iron gets to versus your drier versus your washing machine. The lowest temperature is probably fine, and there’ s a lot of data backing that up. The other caveat there is for the spunbond unwoven polypropylene. If there’s a mixture of other materials in there – polyethylene melts at boiling temperature. So if there’s any of that in the fabric, it’s going to melt and shrink even at the lowest temperature setting on the iron. So make sure it’s 100% polypropylene. The NWPP doesn’t shrink at all at 150F [?]. I tested five different cycles of steaming. With Polyethylene, it shrunk by 20%.

ETG: Could you spray the mask with alcohol spray? Is that going to do anything?

Songer: I vote washing, boiling or steaming. Whenever you start spraying chemicals onto it, you have to be real careful with residues and what you are then inhaling. Those solvents can also break down some materials more quickly. In general, I don’t recommend it.

A lot of people are getting little UV boxes to put their masks in to sterilize them and disinfect them. I don’t recommend that for masks. It’s good for materials that are hard and not porous, but masks have multiple layers. So the known challenge is that UV doesn’t penetrate through all the layers and all the seams. So in general, it’s not recommended because it can’t get to those middle layers.

ETG: You have a ton of this information and more on makermask.org.

Breathability Data

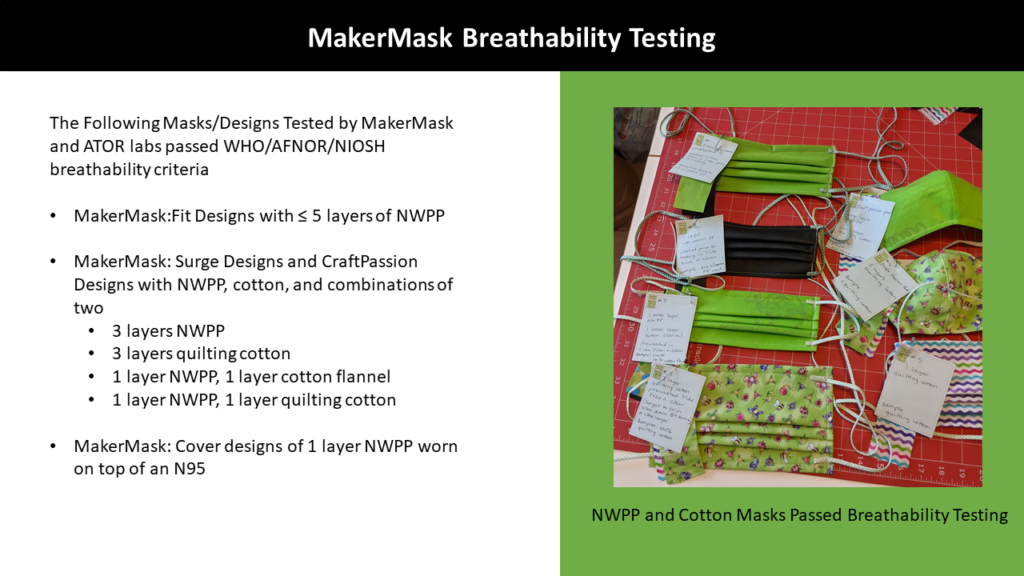

18. MakerMask Breathability Testing

Songer: We’ve got some breathability testing on the webpage for a MakerMask cover which is a single layer of NWPP on top of an N95. We also tested the MakerMask Fit [inaudible:234:24] design and it has breathability showing that for less than five layers of NWPP that works out. Then the data we have showing the NWPP and cotton combinations: I’ve got a picture of a whole bunch of MakerMask Surge designs as well as some of the Craft Passion designs looking at the breathability for three layers of NWPP, three layers of quilting cotton and then combinations of NWPP and cotton. We haven’t managed to get that data published yet, but all of those combinations were breathable. So this reinforces that you can do your two layers of cotton and a layer of NWPP on the outside. The filtration meets the WHO standards with those combinations as well.

Closing Remarks

19. Thank You

Thank you.

Question and Answer Session

Participants: Dr. Jocelyn Songer, Dr. Elizabeth Townsend Gard, and Joel Sellers

Joel Sellers: We made 25 different combinations. What it really helped with was looking at what was easier to sew. The slippery stuff was all hard to sew, especially when you do it quickly. The two and three layers of polypropylene were tough on the needle. It’s heavy-duty stuff.

Songer: We have a needle recommendation up on the website of 16.

Sellers: I think it may even be an 18. We ordered a bunch of fabric any time we saw polypropylene. Some of them were woven; some were solar.

Songer: A lot of those have UV coatings on them, so that’s another flag.

Sellers: We got a lot of this stuff through Jo-Ann’s, and it had all the information about it. So you’re thinking this may have chemicals that are probably not the best thing.

Songer: Yeah. So a site that often gives that information is SailRite, which I’ve used when I make source materials for outdoor gear. I know that they have one of the lighter-weight polypropylenes. I haven’t ordered from them yet.

Sellers: One of the easiest and least expensive was the Pellon 915. It’s a non-woven, non-iron-on Pellon. It was less than $2 a yard. It sewed very easily; it was very breathable; very comfortable. What I wasn’t sure about was durability. We put some sort of quilting cotton on the inside of all of them except those that wanted just two layers of silk or satin. That was for comfort; I can’t wear that scratchy stuff next to my face.

ETG: Is the thinness a problem? We could put two or three layers of it. Is that better than thickness in terms of polypropylene?

Songer: The thicker stuff tends to hold up better and longer. If you’re putting it through the washing machine, I recommend putting it in lingerie bags. I tend to like to do an outer layer that’s one of the heavier ones, but what the WHO study and guidance show is that one of the nice things about the lighter-weight polypropylenes is that you can layer them and keep the same Q value. They specifically talk about interfacing. The material they’re using is I believe 30 GSM, which has a really high Q value so it’s good for filtration and particle filtration. They added five layers of interfacing at 30 GSM each, so that’s 150 GSM, essentially. It’s still lighter weight than a lot of other materials.

Sellers: Someone thought this was polyester, and many interfacings are, but Pellon 915 is polypropylene.

ETG: We can find out what the GSM of it is.

Songer: That’s something we can test at home, which is really useful in having conversations between sewists and scientists. You can get a kitchen skill which will measure 5 grams or less. So you take your square of fabric and see how much it weighs for a given area – either ounces per yard square or grams per meter square. Then we can at least have one of the parameters the same between us.

ETG: What’s the goal on grams to get to?

Songer: They don’t give you a goal in grams to get to. They were trying to get a certain total particle efficiency. They know from the Q value that you can layer it together and get the same ratio of filtration to breathability. To get 70% particle efficiency, you stack the layers. The more layers you stack, the more filtration you get.

ETG: You could easily do five layers with the Pellon.

Sellers: I can certainly try it. Trying to make the pleats is a little bit tricky when you have lots and lots of layers and it’s very heavy.

Songer: I’ve made a few with five layers of a 40 GSM material. That’s less thick than a shopping bag at three layers, and it is the most breathable mask I’ve tried so I’m really excited. I sent it off to get particle testing done on it. I don’t know if it will make it through five wash cycles and how the properties change over time with washing. We may be able to help solve this together if we can get coordinated so we’re doing the same sort of home experiments and sharing data with each other. There are a lot of us.

Sellers: This one is two layers of shopping bag and one layer of quilting cotton, and it’s really not a problem. It’s fairly easy to wear; it wasn’t bad to sew. Our comment was that our cotton masks are so much prettier, but that’s a minor detail.

Songer: We say it’s a minor detail, but humans are social creatures and we like to have flare and ways to express ourselves. As an engineer, I just want it to be functional; I don’t need it to be beautiful. I can select different colors; what more can you ask for? But my mom gets that extra flare in there with the cloth ties. And if you have a cloth material inside a cotton with a pattern that you like, and you roll it into the nosepiece rather than out, then you get color across the top and the bottom.

Sellers: We made some using silk and chiffon, and as always you’ve got to pin the heck out of them because they’re slippery.

Songer: The only way I could make silk work was hand-sewing it. So I have some that are two layers of NWPP with silk on the inside instead of cotton, which meets the WHO criteria. The silk and NWPP generate their own electricity. I don’t think it’s enough of an effect for it to be meaningful, but in dry conditions it works. It’s soft and comfortable, but I find that the silk is also warm. For me, both the silk and the cotton end up feeling warm because they’re absorbent and trapping that moisture by my face. It feels really nice when I first put it on and it’s cold out and I’m not worried about being active.

Sellers: We did some flannel masks in the winter, which we will never wear down here. The quilted one, I just quilted a couple inexpensive pieces of fabric. But I wasn’t sure why…

Songer: The rationale there is in both commercial masks and the WHO guidance, they ask you to put a nonwoven layer in the middle because it does well for the particle filtration, and that remains true. It’s just you then have a 2-3-inch…

Sellers: There are the two-part patterns with the seam down the center that is more fitted around the face versus the rectangular with the pleats. Does that make a difference?

Songer: The standard that the WHO references, which is the French Standardization Association, they have strong feelings about that. They say you should not have any vertical seams in the middle of it. Because if you’re concerned about all the particles that may or may not be going back and forth, having a seam going straight up through the middle in the center of the mask has holes from the needle. That’s one of the advantages of pleated masks is you don’t have a seam line up the middle. As an outdoors person, I have a lot of experience doing waterproof seams, so it is possible. But if you do have a seam up the middle, you would want to make sure that things aren’t leaking straight through it.

So the quick home test I do – I’m using water-resistant material so that makes it easier – is I go to the sink and I see if there’s water dripping through the seams. That’s not nearly as small as the 0.3 micron particles that higher-level masks get tested with, but that’s the concern there is that you’re losing efficiency by having holes going up the middle. Waterproof seams aren’t well tested yet for facemasks.

ETG: We really want to keep working with you. There’s a ton of people that are asking a thousand questions. Really, the goal is to take all these questions and the samples and think through all these things and put out something that is really made for the sewing community. It’s really important for us to know these things.

Songer: I should have met you at the beginning, too. I’m an engineer, and I’ve done the research and the science. But being able to communicate something as an engineer to other engineers is different than being able to communicate with sewists.

ETG: One more question: These masks seem to protect me a bit more. Am I right about that? I think that’s a good message that we should be getting out there that it isn’t just about…

Songer: It may act as a bit of a barrier. We don’t have the science to prove that it can protect the user. But I designed it with that in mind. I didn’t want bodily fluids to go from one side of the mask to the other side, so that’s why I focused on those water-resistant materials. I was used to thinking about you get blood or spit or anything on a mask that’s an absorbent material, then you end up with it on your face on the other side.

ETG: We have engineers and textile scientists and chemists listening. This is Becky: “I’m an engineer and a sewist and we’ll get the info out. You have got a team behind you that love you and are so excited that you’re here.”

Songer: If we can develop things together, there’s so much we can do to get things tested and make things better. Masks are better than no masks, but that shouldn’t prevent us from continuing to work to be better. For this pandemic, droplet precautions and droplet protection is working, which is awesome. And we see how far we’d have to go from where we are for something that does better at particles. There’s so many things for us to get better at, especially testing. That’s exciting and sometimes daunting and overwhelming.

ETG: This is the beginning of one conversation. We have everybody’s email; we’re going to connect to people. We will work with you. We love you. Thank you so much for your time.

Songer: Thank you, thank you, thank you to everybody who’s been pouring their hearts and souls into making masks and getting them out there. Data now shows that we are making a difference, and as more data comes out hopefully we’ll be able to get better and better.

ETG: Can we put little pieces of polypropylene in all those filter areas and just sew it back up on all the ones we’ve made? I know it’s going to have cotton on the outside, but we’ve just got a lot of these already made with holes in them.

Songer: I’m okay with that.

ETG: We’ve got a lot with filters in the middle, so we’ve got to figure out how to adapt those. And then going forward, we’ll do the polypropylene on the outside and cotton on the inside. But we’ve made hundreds of thousands of these.

Songer: I know. We need numbers on that.

ETG: We’re going to work on that. We will be in touch with you. Thank you! We all love you!

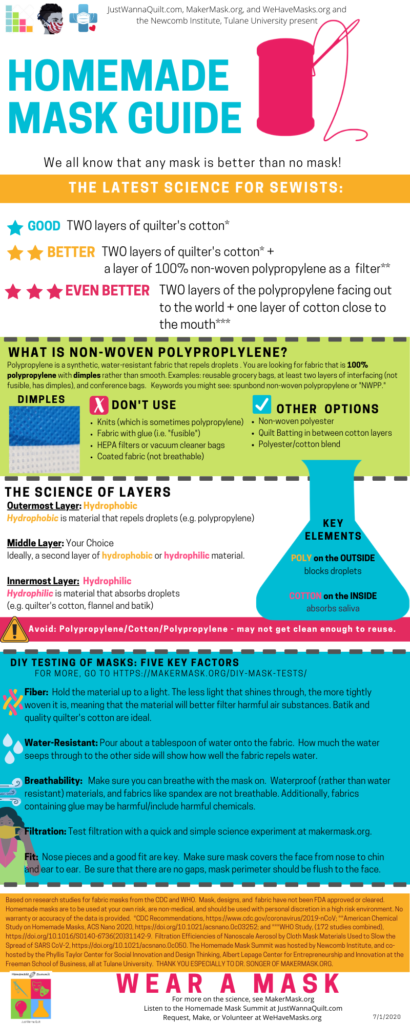

Homemade Mask Guide

At the Completion of the Homemade Mask Summit, the Homemade Mask Guide was created as a collaborative effort between sewists and scientists from JustWannaQuilt.com, MakerMask.org, WeHaveMasks.org, and The Newcomb Institute, Tulane Univeristy. Check it out below:

Just Wanna Quilt Podcast: COVID-19 Masks with Dr. Songer (June 15, 2020)

Transcript: Covid-19 Masks: Dr. Jocelyn Songer of MaskMaker.org joins us – Part 1

June 15, 2020

Transcript edited for brevity/clarity.

Participants: Dr Elizabeth Townsend Gard, Dr. Jocelyn Songer, Whitney, and Alexa

Podcast Introduction

Elizabeth Townsend Gard (ETG), Host: We had a delightful evening with Dr. Jocelyn Songer. She is the founder of MakerMask.org and also a biomedical engineer. She has outdoor experience with backpacking and emergency services and breathing. She has been testing masks and has a strong belief as to what material we should be using for masks. We went for an hour, and then we decided we needed to chat more and chatted for another hour and a half.

So this is part 1 of 2 of a very long, in-depth conversation with Dr. Songer. She is going to be our keynote speaker for our Home-Made Mask Virtual Summit this coming week.

Opening Questions: Dr. Songer’s Background

Dr. Jocelyn Songer (JS): I’m Dr. Jocelyn Songer, and I’m calling from Orange, MA.

ETG: Awesome. We ask everybody this question: Do you have any memory of anyone sewing or quilting in your life? If so, what?

JS: Absolutely. Both my mother and my grandmother sew; my grandmother was a seamstress. She would look after me, and I pestered her forever to let me use the sewing machine, which at eight years old probably was never going to happen. But she did let me use a needle, and she and I did work together to make dolls. She helped me make little patterns, and we would go back to the drawing board a zillion times. But eventually she’d kind of zip one together and then let me do the stitching work. So I have lots of fond memories.

ETG: So what was your life like November, December, six months ago?

JS: Six months ago I was balancing my work on neuromodulation and neuro/biomedical engineering with backpacking.

ETG: Tell us a little more about both. Tell us what that is and a little bit about your path of how you got there.

JS: So my background is biomedical engineering and electrical engineering, and I’ve always been passionate about health and helping other people. I’ve maintained certifications as a first responder. I’m very geeky; I have a very science and engineering mind, so I’ve applied my energies towards developing innovative clinical tools for diagnostics and treatment.

ETG: Very cool. Give us some examples so we can have a concrete understanding.

JS: A lot of the work that I’ve done has been on hearing and balance in the inner ear. So understanding how a hole in your ear can make you lose balance.

ETG: How did you get to that? How did you want to be doing that?

JS: When I was young, I loved health and science. My mom is a nurse, so I was passionate about that. I saw a talk on the brain, and what is cooler than how the brain interfaces with electronics and electrical devices. So that is what nudged me in that direction. Early in my career, I got interested in the ear and the acoustics of sound because cochlear implants was where the brain met electronics the best. Then there were some real-world clinical challenges people were finding where this hearing and balance stuff was interacting. So I studied acoustics of sound and how it’s produced and how you hear it, and that kind of led me into the brain.

ETG: Very interesting. So you’re going along; you’re backpacking; it’s great. Then what happens?

JS: So I am asthmatic, so I have to pay really close attention to when there are respiratory illnesses getting big. I flew to a conference in January and was already concerned about COVID so I had masks that I was bringing with me. I’ve hiked across the US three times now, so I’ve had to have masks with me at all times or to be able to make DIY masks as needed because of forest fire smoke. So hiking across California, New Mexico, Oregon, Washington, Colorado, Montana where there are forest fires 24-7, and you can’t get away from it because you don’t have a house; you don’t have shelter; you don’t have running water. So you have to figure out how you’re going to make traditional and nontraditional solutions come together so you can breathe. For me, breathing is a privilege. Most people don’t think about it very often because they can just do it, but since 2009 I haven’t been able to take breathing for granted.

ETG: Me either. I had a couple of pulmonary embolisms and they didn’t go away. So yeah, not breathing is really awful. If you’ve experienced not breathing, it sucks – gasping trying to get air into your body is not fun.

JS: It changed the whole way I had to interact with the world. I had occupational asthma. I was literally allergic to my job, so my whole life kind of shifted.

ETG: What was your job that was causing that?

JS: I was doing research in a facility that had fuzzy, furry critters, and I became allergic to them over the course of five years. It happens to about 80% of people, and I was from a small subset that went on to develop asthma. But as a vet, I have all this background and real-world experience in particles and what size they are and how they disburse in travel because I wasn’t the one working with the fuzzy, furry critters I was most allergic to but certain sizes of particles travel and distribute more. I had worn an N95 daily for occupational work, so I had some real experience with how they are not always the most fun things to wear or the most comfortable. Similarly, I hiked with N95’s in the desert – reusable ones while I was backpacking. So I watch TV now and I see all these people with masks that are worn improperly just covering the mouth and not the nose, and I’m like: “Oh, I so understand that…”

ETG: It’s too exhausting; it’s awful.

JS: It’s too exhausting, and it can be uncomfortable. So you kind of shift it; in the desert I did that with the smoke because I would be hot and sweaty but I needed something, and it helped. It sort of highlights some of the differences between when you’re wearing a mask for infection control, essentially in a pandemic where the things that you do to treat with forest fire smoke or other things where you’re like, “well, if it’s preventing me from breathing through my mouth, but all that stuff is coming out of your nose…” So every time I see it on TV, I’m like: “if you can’t wear the mask…” The most important thing about a mask is your willingness and ability to wear it when you need to be wearing it. So if it’s an N95 and it isn’t perfect, that’s okay if it’s a mask that you’re willing and able to wear for the amount of time that you need to wear it.

So I feel like some of those human factors are things that don’t get talked about very much. I make my masks, and I know the science really well, which helps. I have experience as a first responder, so I’m used to thinking about these things.

Mask Research

ETG: So we’ve been doing research; we’ve been talking to different people: industrial hygienists and all kinds of other people. We’ve learned about big particles and tiny particles and electrostatic fabric versus cotton and all this stuff that tells us where we’re at.

For those that want to follow along, go to makermask.org.

You’ve got a science-based resource on creating masks. We’re doing a summit next week, and the goal is to gather everything. There’s so much science out there, and we really want to be able to make masks for our friends and family and communities – first responders if they need them again. But there’s too much science out there; it’s chaotic. So tell us about your science. You design water-resistant, non-woven, polypropylene. We just got some polypropylene that’s latex-free and can be machine-washable or disinfected by boiling or autoclaving. So tell us what that is and why that’s important and how you make your masks.

JS: I initially started from the infection control standpoint. What we know most about COVID-19 and the transmission of SARS-COV-2 — which is the virus associated with it – is that it’s mostly transmitted through droplets. There’s a whole long dialog about the different forms of transmission, but for droplets in hospital settings, it means that they wear surgical masks, gloves and gowns. The surgical masks in those cases provide droplet protection, which means they prevent water-based droplets from coming through and those masks are water-resistant. So they’re designed to block bigger particles and especially particles that are in water. That’s why I started looking for water-resistant materials is to block droplets so that you can contain your droplets to you and keep other droplets out.

Polypropylene

ETG: It’s a great website because you’re also suggesting what is polypropylene on there, right?

JS: Yeah. I was used to thinking about polypropylene from backpacking because all of these synthetic fabrics and high-tech materials are really popular there. But most of those materials are woven, so the big stuff goes right through it. The challenge is finding something that’s water-resistant so it provides a barrier to droplets; that’s breathable; and that you can wash, clean, sterilize, disinfect. So you have to have the trifecta there. Reusable grocery bags are nonwoven polypropylene. It’s really hard to talk about because people are like: “I’m not going to put a bag over my head!” Absolutely, don’t put a bag over your head. The key is it’s got to be breathable; if it’s not breathable, don’t use it. That’s rule number one.

It turns out that these reusable, nonwoven polypropylene bags, which I shorten to NWPP, are designed to be touching food, which is good because they meet some standards; they’re designed to be washable so they can be disinfected; and it’s water-resistant because you don’t want the wet stuff from your food soaking into the bag. So it met all those criteria, so that’s how I ended at nonwoven polypropylene from reusable bags. It’s because of that food-grade component that made me select that relative to other things. It feels like fabric, and you can find it in all sorts of sources around the house like with the food grade but in other things like interfacing, which sewists are much more familiar with. There are lots of variations, but you can get nonwoven polypropylene in interfacing. The caution there is that most of the interfacing that people are used to is fusing interfacing.

ETG: Right, so you want non-fusible?

JS: Right, because fusible has adhesives. Breathing in adhesives is usually bad.

ETG: And stabilizer? They have stabilizer that’s not fusible.

JS: Some of the stabilizer if it’s backing that’s tear-away for some embroidery projects, a lot of that is also nonwoven polypropylene. They’re different weights. I feel like I’ve been down the rabbit hole on nonwoven polypropylene and looking at all the different kinds with different safety and engineering features because when you’re making something, you want to make sure you’re not doing more harm than good.

Whitney: I think that’s why we’re trying to do the summit is because there are so many sewists and quilters out there who want to help and make masks, but there’s so much information and some of it’s conflicting, and it’s like what do we do because we just want to do the best thing.

JS: I want people to wear the masks that they’re going to be comfortable with and that they can get or create. A lot of people have been focused on making a zillion masks and getting them out as quick as possible. As a scientist, engineer and researcher, the thing I can do is take a deep dive on all the science and come at it from the health perspective, too. But there’s so much information that figuring out how to communicate it to people who are sewing masks, wherever they are, more effectively is the thing I struggle with.

ETG examined some nonwoven stabilizer.

JS: The polypropylene in particular that I’m looking for is called spunbond. That gets into the details of how it’s made. But if you look closely at the bags, they have this little pattern to them that looks almost woven.

ETG: This one is flat.

JS: I think what you’ll find is that if you go to tear it, it tears more easily than if you had some of this other stuff.

ETG: This tears really easily. You want it to tear easily, or you don’t?

JS: You don’t want it to tear easily. If it tears easily, it’s not going to hold up as well to washing.

ETG: So for single use, it would be okay. It’s just the washing factor that you’re concerned about, is that right?

JS: Right, the durability. If you’re going to wash it and try to disinfect it to use it multiple times – especially if you’re putting it in the middle layer of a mask, you don’t know how it’s holding up.

ETG: So you just want the basic one that doesn’t have any extra bells and whistles.

JS: Right. If you’re on the webpage, there’s a section called Research Blog. If you page down in there, there’s a place called Big Four: Criteria for Community… That one dives into all of that…

Water Resistance

ETG: Tell me a little bit about the fluid resistant test.

JS: In the US, for something to be called a surgical mask, it has to be fluid resistant. The FDA has really strict conditions for what that means. There’s one specific test that it has to pass which uses synthetic blood. That’s for surgical mask classification. Most of us who are just trying to make masks for community use for friends and family, water resistant is much more easy to check at home to see if it’s going to provide some barrier to water. The simplest version is you just flick water at it and see if it beads up on the surface. If it beads up on the surface, it’s hydrophobic and water resistant, and if it absorbs into it, it’s not; it’s hydrophilic. With the mason jars, you can measure it and quantify it, which makes the scientist in me really happy.

Mask Designs and Layers

ETG: Let’s go back to the masks that you’re making. You have Cover, Surge and Fit. Let’s talk about Surge and Fit because Cover is the N95, and that’s not really where we’re at I don’t think.

JS: Although I’ll mention that WHO has released new guidance on fabric masks. Three layers, including nonwoven polypropylene.

ETG: It’s like they knew you.

JS: One of the things with the Cover is that you could use it over cotton masks if you wanted to have a layer of water resistant over materials that are more water absorbent.

ETG: So, the Surge is the pleaded masks a lot of people have been making. It’s got three layers, and it’s got the pipe cleaner across the top so you can fit it. Do pipe cleaners wash okay?

JS: If you sew them in, they’ve been rewashing fine. It’s on the Surge guidance as two; I find it works better with three because it makes it a little bit stiffer and you get a better fit.

ETG: Three together?

JS: Yeah, I push them together. What I’ve found I love to put in the nose pieces are the ties that go around coffee bags. There are a number of different things you can use to stiffen across the nose as long as it fits.

JS: I forgot to mention that when I wash the ones with pipe cleaners or any other nose bridge, I put them in a lingerie bag because otherwise they get bent a lot.

ETG: So you’re doing three layers and they’re all polypropylene. You’re not doing a cotton layer. How do you feel about cotton?

JS: The nice thing about cotton is everybody has it. For all these other materials, we’ve had challenges sourcing them. Initially, the masks that you could get people wearing as quickly as possible were the best. Cotton tends to be absorbent.

ETG: Which is bad…

JS: I think absorbent is bad for the outer layer of the mask because what I want to do is make sure that I have a water-resistant layer that isn’t going to…

ETG: So one polypropylene layer on the outside.

JS: Yeah, at least one polypropylene layer on the outside. That way if anything with moisture comes at you, it can shed and fall off, and your droplets don’t spread beyond the other side.

ETG: How do you feel about cotton on the inside?

JS: I’m okay with cotton on the inside (against the face). It’s more comfortable for a lot of people because they’re used to it. It absorbs the moisture so it kind of keeps it close to you. If people are worried about the synthetics touching their skin, cotton is good. I still recommend and prefer the nonwoven for all three layers. Part of that gets into the washing and cleaning and drying aspect. Nonwovens dry faster, whether it’s from your own moisture or from washing. It dries really quickly, so that’s less time that you have a warm, moist environment for things to grow in it. So I prefer using different weights of nonwoven polypropylene for the different layers. The default instructions say use three of the same because up until now we haven’t had a lot of variety in where we can get nonwoven polypropylene materials. So if you only have the bags, you can use that for all three. That is not as comfortable as the nonwoven polypropylene in garment bags and other sources. The inner-most layer of the mask for me is mostly about fit and comfort. I rely on those other layers to provide the barrier and filtration and all those other features and factors. I increase the number of layers if I want more particle protection.

ETG: How far do you go?

JS: The very first thing that I did after developing the masks, designing them and proposing them and researching the heck out of them was send them down to ATOR Labs in Florida to get breathability testing done on them. I have been searching for all the other testing ever since. Where I haven’t been able to get professional testing done, I’ve come up with DIY procedures to test all the critical elements. For the professional lab testing, we got ATOR Labs to work with us, and they provided breathability testing: inhalation resistance, exhalation resistance, CO2 accumulation, for all of our mask designs.

ETG: How did it go?

JS: It went well. That was what slowed the initial – I wasn’t willing to put this stuff out there until I had seen that it was at least breathable. We’ve looked at the safety data sheets, and we’ve thought about different potential hazards, and we’re confident that we’re not going to do more harm than good. I tested up to five layers of the NWPP, and they passed the breathability criteria. They also pass the French standard referenced by the WHO. I’ve got some of that data up on the webpage, though I haven’t been able to get it all written up.

Mask Fit

ETG: Tell me about fit because we’ve heard that the fit is really important; if it doesn’t fit right, the percentage of protecting goes down real fast. What are your thoughts about that?

JS: The challenge here is you have to know what it is that you want your mask to do for you. Masks are like shoes: sometimes you wear sandals, sometimes you wear sneakers, and sometimes you wear mountaineering boots. You wear them to do different things, and the same shoe doesn’t fit everybody.

ETG: We saw with the Olson masks and these other masks that are flat, they didn’t fit very well and you had to have the right face and the right mask. So we went back to surgical because we didn’t know who was going to be wearing them. We wanted my husband who has a big head and my daughter who has a small head to both fit.

Filter Pocket? Yes or No

ETG: I’m curious what your thoughts are on the whole filter pocket thing.

JS: That ties into the fit of the mask in terms of acoustics and airflow. Essentially, the air is going to follow the easiest path. So if you have a really good filter in the middle of the mask and it doesn’t go all the way to the edges of it, the air is just going to go out and through the edges. And if it doesn’t fit well on your face, the air is just going to go out the sides or up through the nose around the eyes. The nose piece is super important in that respect because if you don’t have that nose piece, the air is preferentially going to be going in and out through the space by your eyes. Pulling all the air you’re breathing past your eyes is a bad idea for infection control. All these people show these videos of them with a mask on and trying to blow out a candle, and they’re really excited because they can’t blow out the candle with the mask on. I just do a facepalm on that because I can watch the air going out the sides as they breathe because now the air is going through the mask. So if the air isn’t going through the mask, where is it going? What it means is it’s found an easier path out the sides or down the bottom or around the eyes.

ETG: So do the polypropylene ones allow the air to go in and out and not the particles? Is that the idea that it’s keeping the little particles out but the air back and forth in and out?

JS: Right, and the water out. Because the droplets contain the particles, if you’re keeping those droplets out and you have water resistant, you’re keeping the water out but allowing the air to go through. That’s your balancing act. Same thing with particles: Keeping the particles out, allowing the air to go through.

Ear Loops or Head Ties

ETG: You’re using straps and not elastic. We did, too, because it’s a better fit. The elastic was a chaotic mess in our house with big head, little head. But the straps work really well.

JS: and you can individualize straps as well so you can adjust for different head sizes. And elastic stretches, so as your face moves, the mask moves and shifts. Having the ties helps prevent that. The other issue is latex; most elastic you get contains latex. The first reason why we moved away from using elastic was because so many people in healthcare settings have latex allergies.

One of the challenges with all these masks from alternatively-sourced materials is that if you say “cotton” that describes a huge range of things; same thing for polypropylene.

Material Sourcing

ETG: There was a study that came out. They went to Joanne’s and Wal-Mart, which is totally weird. From a sewing point of view, there was not enough specificity for us to really be able to use it. This whole thing with electrostatic, man-made fabric, cotton – how do you feel about all that?

JS: I agree. One of the challenges with all our mask-making efforts regardless of which materials you’re using is standardizing so you know the material you’re using is the same as the neighbor down the street and if the guidance is applicable and useful.

ETG: I was so frustrated with the dataset.

JS: Part of that is because the scientists are doing what everybody else is doing, which is finding the materials they have now available at home.

ETG: I felt like there was a discourse disconnect. Why aren’t you asking the sewists? We could tell you. They found a flannel that had a percentage of – it wasn’t a 100% cotton flannel, but we all have 100% cotton flannel. Try to find one that has some percentage of a man-made thing, that’s bad flannel!

JS: As a backpacker, I’ve done a whole bunch of research into fabrics and materials to make my own gear. So I have a stack of all these high-tech fabrics that are ultra-light and water resistant and wind-proof and all these different things. That gets you into the language people use to describe fabrics. That is a real challenge. How do I translate thread count to grams per square meter? I translate everything to GSM because that’s at least a thing I can weigh at home and test and verify where my 400 thread count and your 400 thread count are still…

ETG: The New York Times Article said “batik.” So we bought a bunch of batik and we used it, but we want a little more science in the material for us.

Balancing Material Properties

JS: I think that’s a great dialog to have, though, because the important features are the weave, thread count or fiber density, and the GSM is a weight that at least allows you to normalize things. There are some studies that say denim is great, but they put a little asterisk next to it and say that you can’t breathe through it. But the take-home message is that denim is the best mask material. But if you can’t breathe through it, it’s useless.

ETG: We had a study come out that said one layer cotton and one layer flannel. So we made these, and we sent them out, and we’re in New Orleans; people are like, “you’re trying to kill us!” There’s no way you can have flannel in the South in the summer.

JS: There’s a scale. If what you’re trying to do is get N95, the best technologies in the world for N95s are coming out of 3M, and most people who have to wear them hate them. They wear them for as short a period as they can because they’re hot, humid, and they’re not comfortable. That’s as good as you can get when you’re pouring a lot of resources into this one thing. But to get an N95 that gives you the particle filtration that’s been the focus of the conversation so that you’re blocking 0.1 micron, it is not very breathable, not very comfortable. Most people are not going to wear it well for more than 10-15 minutes before they pull it down or take it off. As soon as they do that, they’re getting 0% particle filtration. So who’s going to wear it? Where are they going to wear it? And how long are they going to wear it? And what’s the relative risk? For a really high-risk environment, you should wear more layers to give you the best particle filtration you can get. I use three layers of NWPP when I go to the grocery store. I have some that’s thicker that gives me a higher degree of protection, but I don’t want to wear that very long. When I go hiking or into the Maker Space that I’ve been helping out, I wear something that’s a little bit more breathable because I can wear that for four hours straight without taking it off and without touching it to readjust it.

ETG: There’s a whole list with chiffon silk, 100% polyester… What are we supposed to do with that? Do we add two layers outside, inside? Are we really spending $40 a yard on 100% silk? Is that better than polyester silk?

JS: It is very different, certainly. When you’re mixing and matching fabrics, the first thing I would say is to make sure that the washing instructions are going to work for all of them. Also, in terms of how it wears out, you that sew a lot, you know along the seams if you sew your chiffon to your canvas denim…

ETG: It’s going to pull out if you’re not careful. The weight differential is going to mess it up.

JS: When people are going down these rabbit holes on chiffon versus silk and not giving us any information about which of those materials they’re specifically talking about, a lot of that is thinking about that really fine filtration.

Electrostatic Filtration

EGT: They’re trying to do the electrostatic for the teeny-tiny drops. That’s how you keep them from getting in.

JS: That’s how you get better particle filtration while still keeping breathability.

ETG: And how do you feel about that?

JS: I feel like it’s a challenging thing that’s still very experimental. For me, it worked well because NWPP holds a charge very well like other synthetics. A study that just came out June 2 is like yay, not only do you have your filtration for lower weight and more breathable materials – 43 GSM interfacing in particular – I think that’s kind of light weight. It doesn’t hold up as well. The WHO guidance specifically says non-woven polypropylene interfacing is a good material to use. That’s based on this paper I was just mentioning which shows the particle filtration, and they show that hydrophobic materials are able to store a charge on them which cotton can’t, and unlike other materials like silk, they keep charge for a longer time. It holds a charge overnight at room temperature. They tested it at body temperature and high humidity and found that it held a charge for at least an hour, which is pretty good. That’s where the guidance for using synthetic layers like nonwoven polypropylene and polyester are coming from. If you roll them between your latex gloves and build up a charge and you do that for 30 seconds, it builds up a charge that can last an hour even in humid conditions to give you a bit of a boost on the filtration. That’s interesting and exciting. We’ll take extra boosts if we can get them. It’s specific for hydrophobic materials because if it absorbs water, it doesn’t keep the static charge.

We don’t know how that kind of treatment is going to impact the durability for reusable masks. If you’re sitting there and rubbing the heck out of it for 30 seconds every time you wear it, that’s going to break it down faster. So like many other things, there’s a trade-off there. I’m curious to see how that pans out over time.

ETG: So on Amazon we’re looking for: non-woven interfacing polypropylene, breathable, dust-proof, anti-fog. Then it’s got one that’s waterproof and one that’s not.

JS: So waterproof and breathable don’t tend to go well together. When I think waterproof, I think Saran wrap. It’s waterproof; it does a great job at blocking particles; but don’t put it over your face; it is not breathable. The most important feature of your mask is that it’s breathable and not hazardous.

Burnout

ETG: People have made a ton of cotton masks; most shops are selling those, too. We may not be making them in the crazy way we were; it got political; companies are making them; people think they don’t need to wear them. I don’t feel that way.

JS: And also burnout. I just want to say to all the people who have been sewing hundreds, thousands, no matter how many, I have seen the most heartening thing while the whole world is falling into chaos for so many reasons. I agree that spending 103 hours a week on masks for months at a time isn’t sustainable.

ETG: It was really exhausting. So going forward, polypropylene is going to be hard for people to get, I imagine. What are your thoughts about a layer or two layers of polypropylene plus cotton plus chiffon. If people are out there freaking out because they have all this cotton but no polypropylene, what do we say?

JS: I would say that the best mask is a mask that you can have, you can get, you can make. So I don’t think we should throw out these other masks. We know the science is evolving rapidly around us. For a long time, my thought is if you have some nonwoven polypropylene, if you can just make a layer of it to wear over cotton masks so you get that water-resistant, hydrophobic layer on the outside…

Mask Layering Combinations

ETG: So the outside is key. You wouldn’t want cotton and then polypropylene; you want the polypropylene on the outside?

JS: I want the polypropylene on the outside, absolutely. I think two layers of cotton inside, one polypropylene outside or one cotton, two nonwoven polypropylene; all those are fine. I would advise against the cotton sandwich where you have a water-resistant, non-woven polypropylene with cotton or some other absorbent material in the middle and then NWPP on the other side because of washing and disinfection. If you’re trying to wash something, and you trap all this warm gunky stuff in the middle, how do you make sure that is getting clean when you have two water-resistant layers on the outside? That may be fine for a disposable mask, but for anything reusable, that’s the sort of thing that absolutely needs validated disinfection and cleaning methods because that scares me in terms of what might grow in the middle.

ETG: Can you do the opposite with cotton on the outside but the polypropylene on the inside?

JS: I think that’s okay. I wouldn’t consider it ideal because anything coming from the outside is going to get trapped in that absorbent layer, and you’re holding it closer to the face. That’s the thing that I dislike about that. But you do still have that water-resistant layer in the middle that’s acting as a barrier to hopefully help keep things from going out or going in. But I have to note that the WHO and the CDC and all the guidance out there right now says that you should be using masks for source control. The only thing you’re concerned about is keeping your germs from going out.

ETG: That’s any cotton mask, then, on that level is okay.

JS: Yeah. Some of them are going to be better than others. That’s why they all say use multiple layers because one layer acts as a diffuser potentially; that gets into a longer discussion. But for what the government and regulatory officials say we should be doing, having just that nonwoven layer in the middle serves that purpose; it helps keep your droplets to you and the other droplets going the other way. If you have an absorbent layer on the outside catching everything that’s being thrown at you, and then it’s drying out, once it’s dried out it’s a smaller particle size. So I don’t recommend having an absorbent layer on the outside. There isn’t any science that I’m aware of yet that backs up my intuition and my view and analysis of why that’s concerning.

ETG: You think three layers of NWPP is the best, but if you have the masks that don’t have that, it’s okay; it’s better than nothing. And if you’re trying to do a hybrid, that’s not super key.

JS: Pretty much. I will say that in terms of what that layer is closest to the skin, I’m not sure. Having that be cotton like the WHO recommends may be just as good as having it be all three NWPP. I find it less comfortable and too warm. There are a lot of reasons why I recommend that three layer. Part of it gets into washing and disinfection.

Washing & Disinfection

JS: There’s a whole blog post that goes into way more scientific detail on that. If you have a mixture of materials and fabrics, especially the absorbent ones, when you wash them with detergent you can get skin irritation.

ETG: You have to use detergents that support allergy return. Fragrance free.

JS: The EPA has a whole site that goes into detail. But if you’re going to use detergents, keep that in mind because you’re holding things up against your face for a long period of time in hot, moist environments.

Transcript: Covid-19 Masks: Dr. Jocelyn Songer of MaskMaker.org joins us – Part 2

June 15, 2020

Transcript

Transcript edited for brevity/clarity.

Participants: Dr Elizabeth Townsend Gard, Dr. Jocelyn Songer, Whitney, and Alexa

Elizabeth Townsend Gard, Host: Let’s start with you and what you really want quilters to know as a scientists coming into this as someone who cares and has breathing issues yourself. What should we understand?

Dr. Jocelyn Songer: I think the first thing is how much we appreciate you, because all of these efforts to get masks to as many people as we can as quickly as we can would not be happening without you.

Second is that even though it’s complicated, it’s worthwhile. Keeping breathability in mind is always an important thing because we’re covering the mouth and nose. We want to do that as safely as we can. So it has to be breathable, and it has to be something that people are willing to wear for the entire time they need to be wearing it.

In terms of the science, ask questions. As long as you keep asking questions, it will force people to come up with better answers. We’re all in this together. We’re all working to create better solutions to make our families, friends, community and healthcare providers safer. We’re doing an amazing job at that even if things may not be perfect yet. Don’t let perfect be the enemy of the good.

Alexa Magyari, Host:

We’ve made all these masks. You’ve proposed a couple solutions in Part 1; one if to make a nonwoven polypropylene cover to go over a cotton mask that we’ve made. You’re suggesting that this is superior to making nonwoven poly propylene (NWPP) filters to put in the filter slot?

JS: I would say yes.

AM: Would you say that making those filters is better than nothing?

JS: Yes.

AM: Do you have any other insights into how to modify these cotton masks that we’ve already made to improve them?

JS: What I would do is if you can put one layer of NWPP and have that go over it, that will give you that extra water-resistant boost. A lot of NWPP is pretty lightweight, and one of the advantages is that it’s really breathable. So you can put a layer of it over an N95. N95’s are not the most breathable or comfortable things in the world, and it’s still breathable. We tested that, and it got a big thumbs up.

AM: So we know how we’re going to fix our imperfect masks of the past if we’re so inclined. Moving forward, the gold standard in your opinion is the three-layer NWPP. In an ideal scenario, where are we sourcing that material?

JS: That is the big challenge. The ideal material in an ideal world is medical-grade spunbond nonwoven polypropylene. There isn’t a great, easily-accessible source for that yet. We’ve got people working on that and trying to coordinate with distributors. But moving forward, that’s what we would like to do is to make it so that as this continues, there’s a place that we can point to where mask makers can obtain materials that we’ve tested and know are great.

AM: In the absence of being able to buy it in bulk, is the best thing to do to cut up my bags? Or is it better to start with the interfacing?